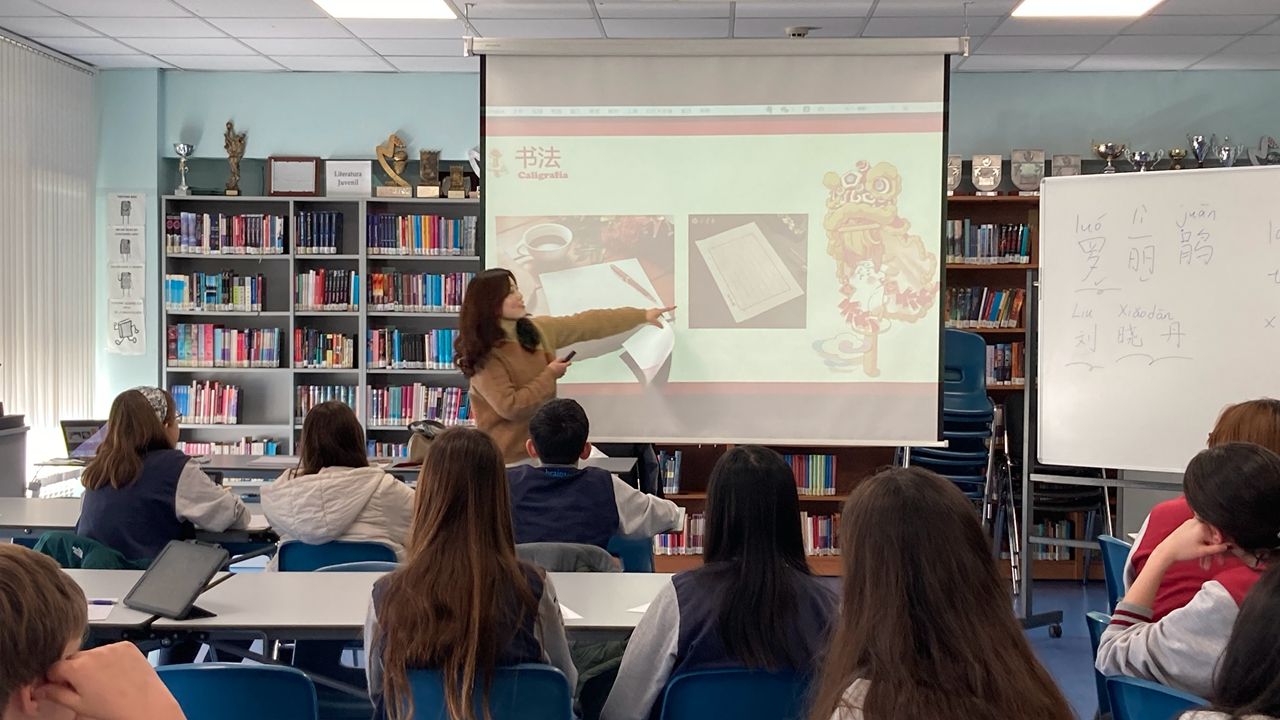

Teaching Chinese in Spain: Exploring the Meeting Point of Two Cultures

Aug 25, 2025

In September 2018, I traveled to Spain to begin an 11-month teaching exchange at Universidad Autónoma de Madrid (UAM), one of the top universities in Spain. As a visiting professor at the Faculty of Philosophy and Arts, I was assigned to the East Asian Studies Center, where Chinese language and culture are taught alongside courses on Chinese history, literature, politics, and economics.

During my stay from September 2018 to July 2019, I taught four different Chinese language courses: beginner, intermediate, and a unique course called Situational Chinese, where no textbook existed—we teachers had to design our own content. For me, this was not just a teaching assignment, but also a chance to explore how Spanish students perceive China and to guide them into deeper intercultural comparisons.

A University with Strong Sinology Roots

At UAM, Chinese language courses are mandatory for students in East Asian Studies, while courses on Chinese culture, history, literature, and politics are electives taught mostly by Spanish professors in Spanish. What impressed me was how structured and serious the program was. Even first-year students in “zero-beginner” classes had to tackle Chinese characters directly—no Pinyin was taught. Teachers presented both simplified and traditional characters, ensuring that students developed literacy in both.

Class sizes were also a challenge: beginner classes had over 80 students, while by the time students reached senior year, the number dropped to only four or five. Another notable feature was that Chinese teachers were required to teach entirely in Chinese, while Spanish local teachers used Spanish.

Designing Situational Chinese: A Bridge Between Societies

The most rewarding part of my time in Madrid was teaching Situational Chinese. Since there was no textbook, I designed the syllabus around student interests. To find out what they really wanted to know, I conducted a survey at the beginning of class.

Students already recognized some Chinese “symbols” like the Tang Dynasty, the Yellow River, kung fu, dumplings, and Li Bai’s Quiet Night Thought. But they were curious about much more: modern China’s economy, technology, cities, films, poetry, food, and higher education.

Based on this, I created weekly cultural themes such as:

- An overview of China

- Chinese economy and technology

- Chinese history and dynasties

- Rivers of China vs. rivers of Spain

- Famous Chinese cities

- Chinese food and culinary traditions

- Chinese classical poetry

- Chinese cinema and TV dramas

- Universities in China

The format was simple but effective: I presented the Chinese side with videos and images, while students had to research and present the Spanish equivalent, making comparisons. After presentations, we held class discussions and students wrote short essays analyzing similarities and differences between the two cultures.

This approach cultivated not only Chinese language skills, but also intercultural awareness, empathy, and critical thinking.

When Spain Meets China in the Classroom

Some highlights from the course:

- Geography & Rivers: Students compared the Yangtze and Yellow Rivers to Spain’s Ebro, Tagus, and Guadalquivir. Discussions revealed how rivers shape national identity and cultural development in both countries.

- Cities: Beijing was compared to Madrid as a political and cultural hub, while Shanghai was likened to Barcelona, the “Mediterranean Pearl” with Gaudí’s famous architecture. Students also connected Suzhou gardens with Spanish heritage cities like Segovia and Córdoba.

- Food: This was everyone’s favorite topic. I brought Chinese dishes such as fried rice, dumplings, spring rolls, and mapo tofu. Students loved it and immediately wanted to try Beijing roast duck, Shanghai buns, Hangzhou’s West Lake fish, and Suzhou’s sweet snacks. In return, they introduced me to Spanish classics like tapas, paella, gazpacho, Iberian ham, and Segovia roast suckling pig. Our discussions went deeper: What do food cultures reveal about national identity? Why do Chinese people greet each other with “Have you eaten?” while Spaniards prefer the slow, social ritual of tapas and wine?

- Poetry & Literature: Chinese poems like Wang Wei’s Birdsong Stream and Su Shi’s Prelude to Water Melody resonated strongly. Some students were moved to tears by Li Yu’s tragic To the Tune of Yu Meiren. In contrast, we explored Spanish poets such as Juan Ramón Jiménez and Rafael Alberti. The discussions showed how Chinese poetry often reflects nature, longing, and philosophy, while modern Spanish poetry leans toward personal memory and social themes.

- Film & TV: Chinese blockbusters like Wolf Warrior 2, Lost on Journey, and Dying to Survive excited students, while classics like The Monkey King sparked nostalgia. However, they struggled with films requiring historical background, such as Youth or Red Sorghum. Spanish favorites included The Spirit of the Beehive, Talk to Her, and The Time in Between. Students noted how Chinese films often reflect collective struggles, while Spanish cinema emphasizes individual emotions and historical trauma.

Reflections

Teaching at UAM gave me invaluable insights into how young Spaniards view China. Through Situational Chinese, they not only learned language but also critically reflected on their own society by comparing it with China. Many told me that Chinese culture was “fascinating and full of surprises” and that they hoped to one day visit China—climb the Great Wall, sail down the Yangtze, and taste authentic Chinese cuisine.

As a teacher, I also learned: teaching Chinese abroad is not about exporting culture, but about creating dialogues where students discover both China and themselves.

After ten months, I left Madrid with warm memories of over 100 students—hardworking, polite, and full of youthful energy. Their curiosity and open minds reassured me that Chinese language and culture will continue to blossom in Spain, adding new layers to the long history of cultural exchange between our two countries.